* Over the last decade, Chinese fishing in Argentine waters has increased by 800%.

** Chinese fishing vessels are present with ships flying the flags of third countries and operating along the edges of Argentina’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

*** The strategic location of the Strait of Magellan and Antarctica heightens Beijing’s interest in Argentine coasts and waters.

By Juan Manuel Harán / Expediente Público

Argentina is a maritime state. Its coastline spans over 5,000 kilometers. The Argentine Sea covers a surface area of 2,804,000 square kilometers, including territorial waters, the contiguous zone, and the EEZ up to 200 nautical miles. When combined with the 2,094,000 square kilometers of maritime spaces in Antarctic waters, this area expands to a total of 4,898,000 square kilometers.

Additionally, 1,785,000 square kilometers extend from the 200-nautical-mile limit to the outer edge of the continental shelf, granting the country sovereign rights over the seabed and subsoil resources.

According to the Argentine Navy’s online publication Maritime Interests, Argentina’s maritime territory is twice the size of its land area, which covers 2.78 million square kilometers.

Subscribe to the Expediente Público newsletter for more insights

This vast expanse of water plays a crucial role in Argentina’s geopolitics and economic outlook, particularly regarding the exploitation of increasingly valuable natural resources, such as fisheries.

Market

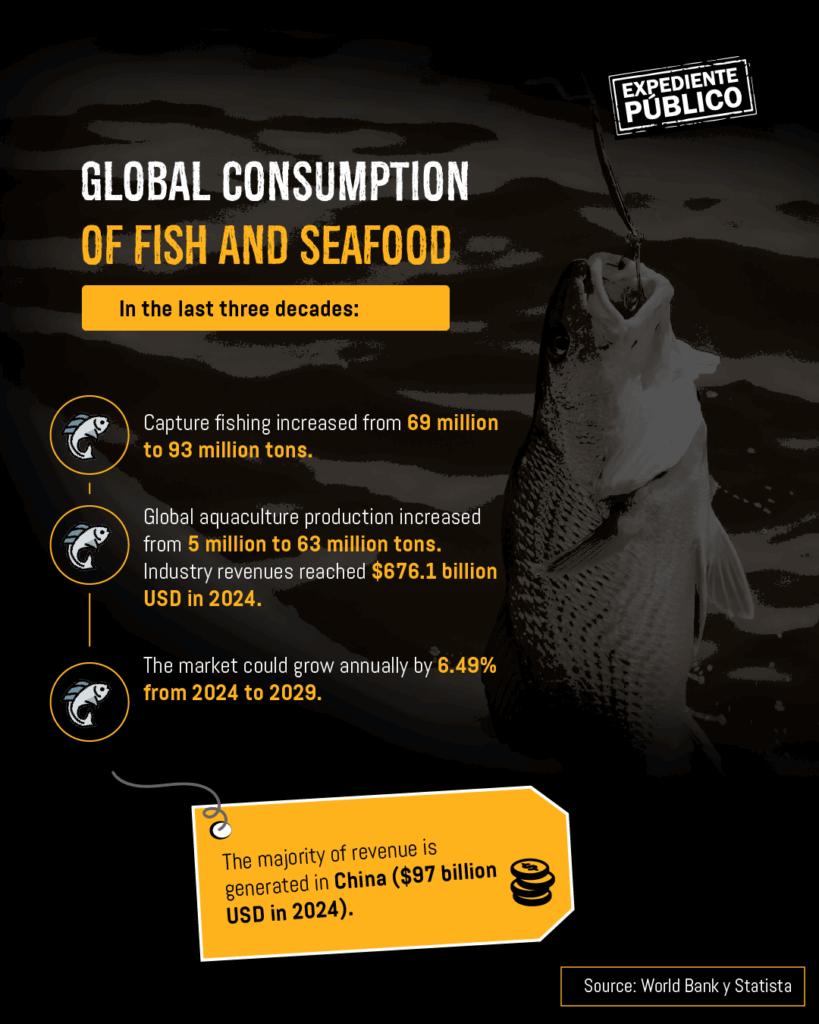

As reflected in World Bank data, over the past three decades, global fish capture production has grown from 69 million to 93 million tons. Simultaneously, aquaculture production surged from 5 million to 63 million tons.

According to Statista, the global fish and seafood market revenue reached $676.1 billion in 2024, with an annual growth forecast of 6.49% from 2024 to 2029.

Globally, most of these revenues are generated in China, which is expected to account for $97 billion in 2024.

This context explains the drastic increase in the presence of China’s distant-water fishing fleet near Argentina’s coasts, followed to a lesser extent by vessels from South Korea, Spain, Taiwan, and Portugal, especially beyond the 200-mile limit of its EEZ.

In context: Milei and Communist China — A Clash with Argentina’s Commercial Reality

Chinese Fishing Vessels in Argentine Waters

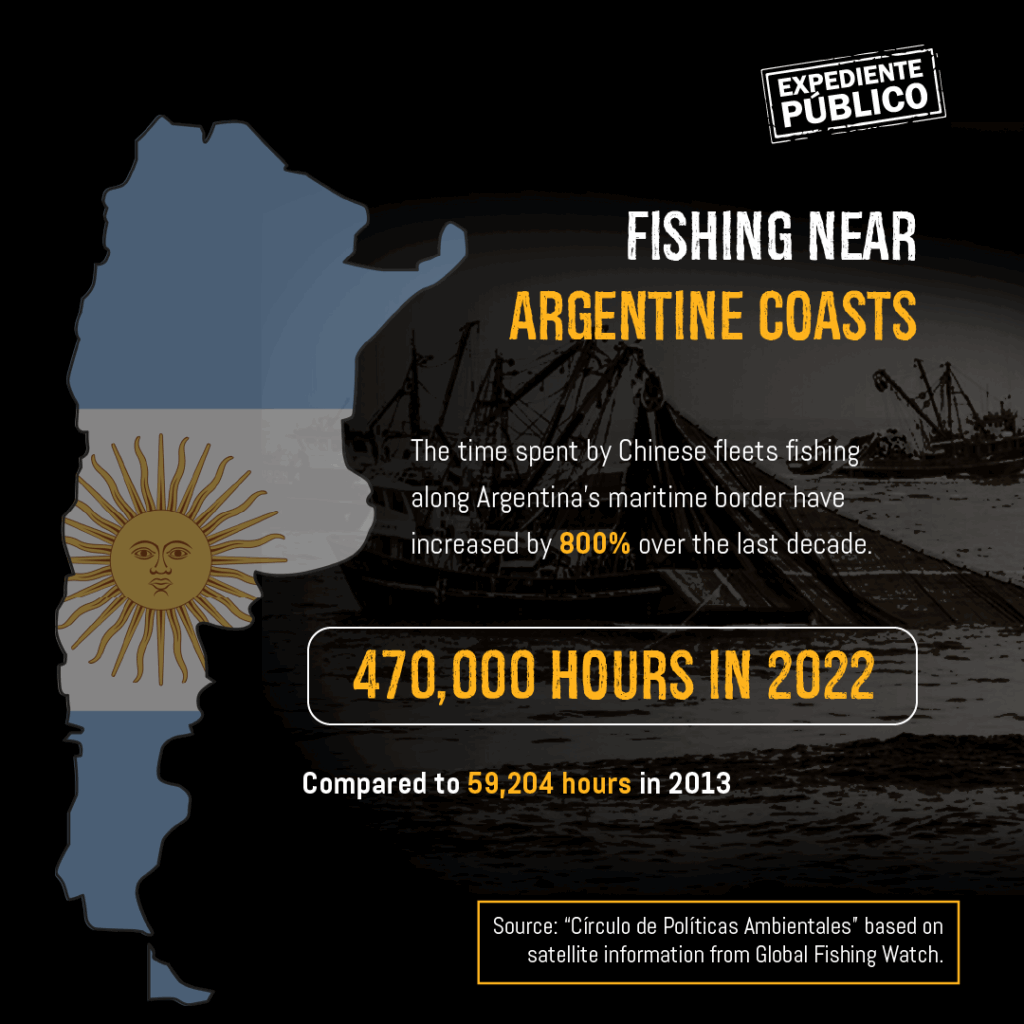

Over the last decade, the time spent by Chinese fleets fishing along Argentina’s maritime border have increased by 800%. This data comes from a study by the “Círculo de Políticas Ambientales”, based on satellite information from Global Fishing Watch.

The report also reveals a significant surge in these vessels’ fishing efforts, which reached nearly 470,000 hours in 2022, compared to 59,204 hours in 2013. These figures highlight the global expansion of these fleets.

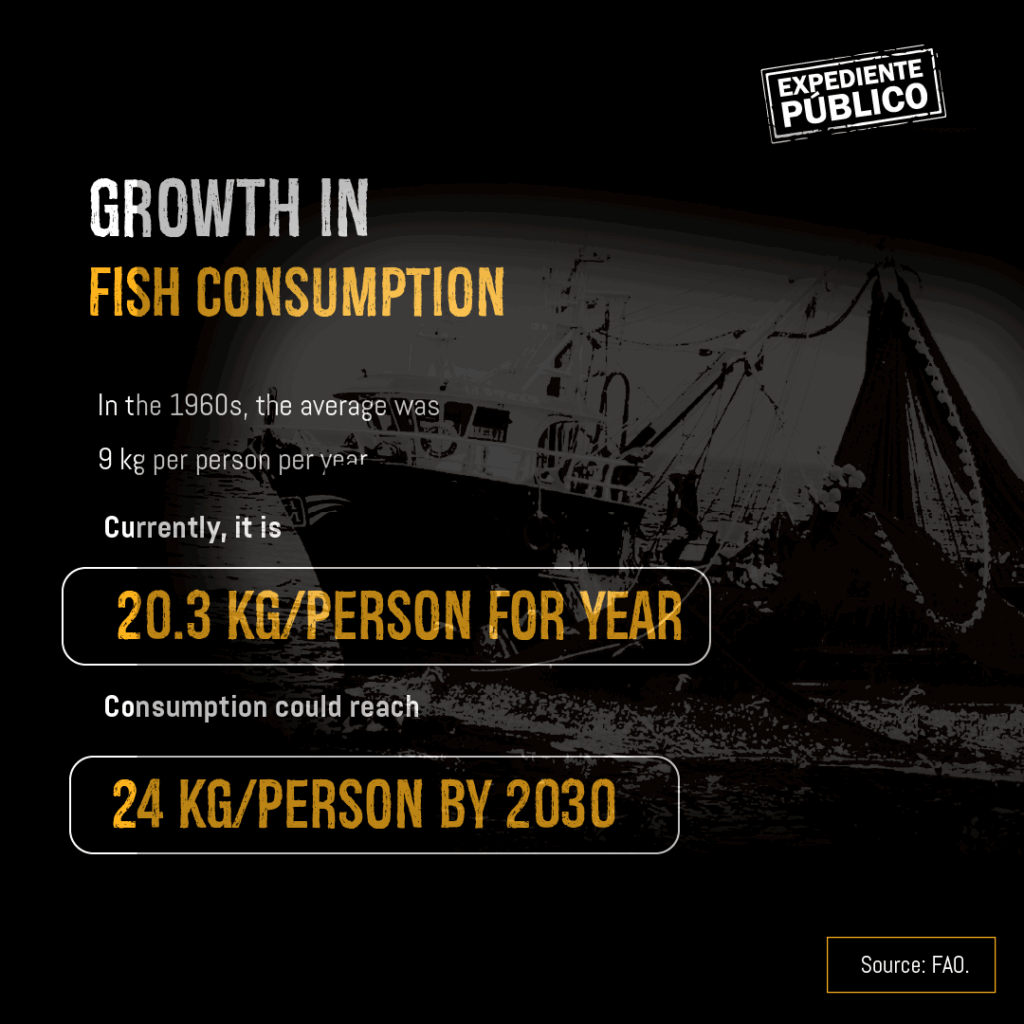

This phenomenon coincides with the rising global consumption of marine products. In the 1960s, average consumption was 9 kilograms per person annually. Today, it has reached 20.3 kilograms per person, with projections from a 2017 United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) study suggesting it could rise to 24 kilograms per person by 2030.

The Powerful and Voracious Chinese Fishing Fleet

In terms of influence, the European Parliament highlights that China’s distant-water fishing fleet is the largest in the world, and therefore, it produces the greatest environmental and socioeconomic impacts in developing countries.

Historically, the sharp increase in China’s fishing catches coincided with the expansion of its distant-water fishing fleet, which began in 1985 when the Chinese sent their first distant-water fishing vessels to West Africa, according to a 2023 report by the European Parliament.

Recent estimates of the fleet’s size place it between 1,600 and 3,400 vessels, although other sources, such as the think tank Overseas Development Institute (ODI), raise this number to as many as 16,000 vessels globally.

At the same time, there is no definitive evidence to suggest that Xi Jinping’s government has complete control over the distant-water fishing fleet, although there are indications of a direct relationship.

For example, data provided by the European Parliament subsidizes its distant-water fleet with $2.4 billion annually for operations in other countries’ Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) and another $68 million for its fleet operating in international waters.

Another characteristic of this fleet is that vessel ownership is highly fragmented among many small companies and includes ships registered in other international jurisdictions, —highlighting the irregularities and lack of transparency in this sector of global fishing.

Related article: Argentina’s Minister of Security: No Strategic Objective Will Be in China’s Hands (in Spanish)

Flags of Convenience

In the case of Argentina, The Outlaw Ocean Project documented 64 vessels linked to Chinese capital operating under the Argentine flag within the country’s EEZ.

This represents a significant number, considering that there are currently 508 vessels with valid fishing licenses nationwide, employing 25,000 people directly and 100,000 indirectly, according to reports from the specialized media outlet Argenports and the Argentine Ministry of Economy.

As another example, the report “Panamá presta bandera a los pesqueros más depredadores”, published by Insight Crime, details how Chinese fleets exploit Panama’s flag through a long-standing maritime practice known as “flags of convenience.”

This was evidenced, among other instances, when in 2020, a Chinese fishing fleet near Ecuador’s Galapagos Islands was found to include 250 vessels flying Panama’s flag.

Chinese Vessels

Reinforcing this view, The Outlaw Ocean Project showed that the Chinese state and Chinese companies have “at least” 250 vessels flying flags of other countries, in addition to the more than 3,000 operating under the flag of the People’s Republic of China.

According to the publication, China’s strategy is to expand its fishing dominance through “reflagging” and to increase its presence in global waters while simultaneously pledging to limit its distant-water fleet.

The case of Panama provides detailed insight into this phenomenon. Much of the country’s appeal comes from its fiscal framework, which creates a favorable environment for shipowners thanks to its open and low-cost ship registry. It allows individuals of any nationality to register vessels, imposes few restrictions on the age of ships, and offers tax exemptions for income generated by vessels under the national flag.

Insight Crime also highlights that foreign vessels can be registered under Panamanian companies, granting shipowners anonymity. This can allow them to evade sanctions, since fleets may be registered under multiple companies—a practice known as “associated ships.”

This model is lucrative for Panama: the cited report estimates that reflagging generates between $125 million and $150 million annually in services and taxes. In 2021 alone, registry fees alone brought in around $87.3 million.

However, the lack of transparency in the fishing industry is not exclusive to China; it also involves other players, primarily European operators of distant-water fleets. For instance, the NGO Oceana has denounced predatory practices by vessels from Portugal, Greece, Spain, and Italy along the African coast, often carried out “with complete opacity.”

Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing: A Threat to Argentina’s Economy

During the high fishing season, from January to July, around 400 vessels approach Argentina’s EEZ every year.

Fishing is a vital source of exports for the South American country, particularly squid (Illex argentinus) and hake. However, illegal fishing reduces the catches destined for international markets, translating into lower export revenues.

Foreign vessels fishing without licenses inside the EEZ and just beyond its outer limits are estimated to harvest around one million tons of marine resources annually.

Based on this volume, the Financial Transparency Coalition (FTC)’s 2022 global report estimates that this practice results in approximately $2 billion USD in annual losses from unreported fish and seafood sales.

To put this in perspective, based on data from Argentina’s National Institute of Statistics and Census, the total value of the country’s legal fishery exports in that same year reached $1.823 billion USD—roughly 10% less than the estimated losses due to illegal fishing.

Figures Increase

Other estimates, such as those provided by the Malvinas Argentina Observatory in the province of Río Negro, place the figures even higher—around $20 billion USD—if one includes the more than 1.08 million tons captured annually by Chinese, Korean, Spanish, and Taiwanese vessels.

As these figures suggest, this irregular activity drastically reduces fiscal revenue from taxes and fees on legal fishing production and exports. It also creates additional costs related to efforts to combat this activity.

This is a concern raised by Sergio Almada, coordinator of the Interdisciplinary Team for the Control of Maritime Spaces and Resources (EICEMAR), senior officer of the Argentine Naval Prefecture (PNA), and independent researcher specialized in maritime crime.

Argentina Loses Out

Mr. Almeda agrees that IUU fishing affects Argentina’s interests—not only economically, but also in terms of sovereignty. The fact that these fleets operate so close to the 200-mile limit “creates a constant threat of incursion, requiring year-round surveillance. The Coast Guard wears out its resources patrolling these waters,” Almada explained.

Regarding the costs involved, in 2020 the Argentine Naval Prefecture charged 86 million Argentine pesos (just under $90,000 USD) in fines to two vessels that had entered the EEZ—one Portuguese and one Chinese.

“We need to understand that the problem is not just the incursions into the EEZ, which are now relatively rare and well-controlled. The real issue is that these fleets remain there for months without entering port, conducting mid-sea transshipments of their catch via refrigerated vessels and reefer containers, refueling and resupplying without docking, and catching the same species as our national fleet—but without any management or sustainability plans,” Almada told Expediente Público.

Unfair Competition

From an economic standpoint, unregulated fleets—unbound by the operational costs, regulations, and environmental standards that Argentine legal fishers must follow—create unfair competition and undermine the profitability of the national fishing industry.

Like any other unregistered activity, it also endangers formal employment and deters investment in the sector. For Almada, another serious concern is the impact on Argentine products in international markets: “When China has a strong fishing season, it floods international markets with prices that are not competitive for our industry.”

He adds: “Likewise, the subsidies these countries inject into their distant-water fleets reduce operating costs, harming Argentine fishing businesses. If they try to export, they lose money. This affects national interests and the country’s economy with resources that were extracted from within Argentina’s EEZ,” the specialist explains.

Lack of Regional Organization

In the article “Escaping the Squid Game in the Southwest Atlantic: Options for Sustainable High Seas Fisheries Management,” experts Cornell Overfield and Jessica Yllemo explain that “much of the high seas is now covered by RFMOs (Regional Fisheries Management Organizations) for transboundary regional stocks.” This means there is some agreement among nearby governments to protect marine life through sustainable fishing. However, the same authors warn that “the South Atlantic remains a glaring gap.”

They explain that territorial disputes—such as that between Argentina and the United Kingdom over the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas)—have hindered international cooperation, allowing foreign fleets, primarily from China, South Korea, Spain, and Taiwan, to exploit these resources intensively, often operating just outside the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of coastal countries.

As an example, Overfield and Yllemo note that “the latest casualty was the South Atlantic Fisheries Commission (SAFC), a data-sharing forum from which the government of Alberto Fernández withdrew in 2020 as part of its tougher stance in the Falklands dispute.”

Territorial Disputes and Lack of Governance

However, they clarify that “at the end of September 2024, Argentina and the United Kingdom signed an agreement to resume the exchange of fishing data, which may indicate that administrative changes have opened the door to practical solutions to regional fisheries issues.”

“Due to limited data collection and sharing, experts from the Center for Naval Analyses are not sure that the current level of fishing is sustainable, especially in the case of Illex argentinus—the Argentine shortfin squid—which makes the region the world’s largest squid fishery,” they explain in their work for the Center.

Overfield and Yllemo argue that “the South Atlantic faces a fisheries governance crisis,” warning that “without concrete action, key resources like the Argentine squid could collapse, affecting biodiversity and local economies.”

A Strategic and Military Step

As explained to Expediente Público by Professor Fabián Calle, an Argentine academic affiliated with UCEMA and the Argentine Council for International Relations (CARI), the United States currently pays close attention to the South Atlantic due to its proximity to Antarctica and its strategic natural passageways: “these are the only places where nuclear aircraft carriers can pass through, since they don’t fit in the Panama Canal.”

“This is evident in U.S. intelligence and geopolitical reports, which used to focus heavily on Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, and the Caribbean. That was their main area of concern, followed by the Andean region, and lastly the Southern Cone,” the professor says.

But the scenario has changed. Over the past 20 years, China has built up its own interests in Patagonia, including the scientific base in Neuquén province, the Cóndor Cliff and La Barrancosa dams in Santa Cruz, which are seeking to restart construction (suspended since January 2024), and investments in the fishing industry, among others.

Also see: China in Argentina: The “Neocolonization” That Devours Everything (in Spanish)

Oil and Gas Deposits

Meanwhile, the strategic location of the Vaca Muerta oil and gas field in Neuquén—a major global shale oil and gas reserve—has attracted numerous international players and has driven investment in railways (such as the Norpatagonian Railway), and ultimately, in initiatives related to the bi-oceanic corridor project.

Additionally, China’s presence in Peru, through the Port of Chancay, built and financed by China with the involvement of COSCO Shipping and recently inaugurated by Xi Jinping during the APEC Summit, also marks the momentum being experienced across the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

Thus, Peru positions itself as the most competitive gateway for trade between South America and Asia, offering faster and cheaper maritime transport services compared to Atlantic routes, as noted in the study “Atacalar in the New Silk Road” by the Catholic University of Córdoba.

That same study also points to a growing trend in Argentina’s imports and exports being funneled through Chile, while the once-dominant Port of Buenos Aires has been losing operational capacity for over a decade, according to the specialized outlet Argenports.

The Importance of the Strait of Magellan

Another factor drawing attention to the southernmost edges of the American continent is maritime logistics.

Since the onset of the pandemic, global trade and industry have been shifting due to China’s economic decoupling and the rise of new industrial and consumer players in Southeast Asia and countries like Mexico, which have been receiving record levels of foreign direct investment from global companies (including Chinese ones), as noted by El País.

Today, financial analysts widely recognize that the drought affecting the Panama Canal and the war in the Middle East could redirect maritime trade through the Strait of Magellan.

According to a report by Americas Quarterly, the Strait of Magellan has become a focal point for the United States due to increased maritime traffic: “In January and February [2024], traffic surged by 25% compared to the same period in 2023, and by 83% compared to 2021, when global supply chains were still disrupted by the pandemic,” the publication states.

This is why a project promoted by China in Tierra del Fuego—the southernmost province in the world, located just 1,000 kilometers from the Antarctic Peninsula—sparked considerable debate.

The proposed investment by Shaanxi Chemical Group included the construction of a multi-purpose port terminal with an internal dock for 20,000-ton vessels, and a 100 MW power plant.

China’s Interest

Although the project has not yet materialized, such initiatives reveal that China aims to operate a logistics hub in the region to support its broader activities.

As Brigadier General Oscar Armanelli, Dean of the Argentine Army Faculty at the National Defense University, told Expediente Público:

“The very establishment of a logistics hub in Tierra del Fuego represents an internal geopolitical strategy for Argentina toward Antarctica. But Argentina will only be able to secure that position if it manages to participate in the negotiations tied to the conclusion of the Antarctic Treaty.”

The Malvinas in the Renegotiation of the Antarctic Treaty

Southern Argentina presents several ongoing flashpoints. In addition to China’s growing presence, there is the long-standing dispute with the United Kingdom over the sovereignty of the Malvinas/Falkland Islands, where the UK issues fishing licenses to multiple countries operating in the South Atlantic, deploys military forces, and exploits resources from the surrounding seabed, according to the Orinoco Tribune.

For Armanelli, this sets the stage for intense negotiations over the administration of a new Antarctic Treaty, amid expectations that the world’s great powers will compete for greater control in the new distribution of influence.

In this context, he believes that Argentina must seek international cooperation regarding the future composition of the Antarctic map, where it shares or overlaps sovereign rights not only with the UK, but also with Chile.

Argentina: An Obstacle to China’s Ambitions

From a geopolitical perspective, Argentina’s presence in Antarctica is seen as an obstacle by major world powers. Summing up this view, Professor Fabián Calle recalls:

“I remember someone once asked Henry Kissinger in 1969, ‘What is Argentina?’ and he replied: ‘A dagger stuck into Antarctica.’”

“At that time, the end of the Antarctic Treaty was still far off. Now, that moment is much closer. Some believe it will simply be extended, but I have my doubts. Clearly, the Antarctic region will be contested by the most powerful players,” the specialist concluded.

China’s presence in the South Atlantic underscores its strategic interest in the Strait of Magellan and Antarctica—regions that are crucial not only for their natural resources but also for their geopolitical importance. Argentina, in turn, faces a monumental challenge: to defend its marine resources and national sovereignty against the growing pressure of a global power.

As the waters of the South Atlantic remain contested, the link between China and illegal fishing stands as a symbol of the complex challenges defining geopolitics and sustainability in the 21st century.