* Invitations to events in China are becoming frequent and uncontrolled, with expenses paid for politicians, journalists, and academics.

** Experts recommend addressing risks, demanding transparency, and maintaining a commitment to liberal democracy in the face of China’s authoritarian pursuits.

Expediente Público

China brought more than 60 legislators from 50 countries to Xinjiang, the autonomous region of the Muslim Uyghur ethnic group, which lives under a strict police state with extensive restrictions on its religious and cultural life.

The so-called Forum of Legislators for Friendly Exchange took place between September 10 and 17 and was notable for the Urumqi Declaration (capital of the Uyghur region), in which they «highly recognize China’s policy on Xinjiang and positively assess the great achievements in its economic and social development.»

In addition, international legislators and former legislators, along with 60 other deputies from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), «oppose the political manipulation of certain countries to interfere in China’s internal affairs,» among other points that demonstrate Beijing’s rhetoric on multipolarity, shared prosperity, and inclusive development.

Subscribe to the Expediente Público newsletter and receive more information

International human rights organizations estimate that at least 120,000 Uyghurs are in forced labor camps and warn that the figure could reach one million people.

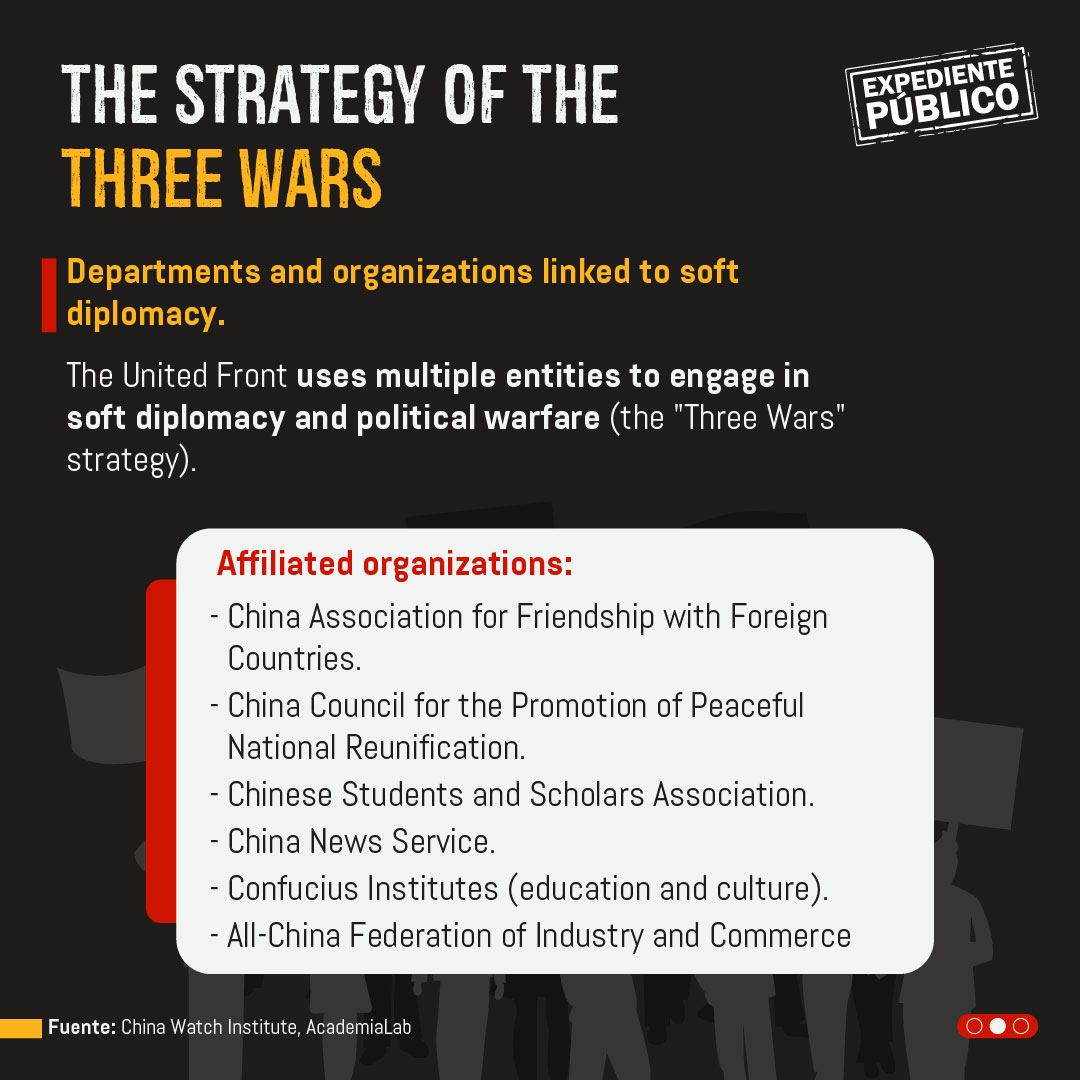

United Front

The Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (CPAFFC) organizes these types of forums. It is an agency within the United Front Work Department (UFWD), an office of the CPC Central Committee.

Henning Suhr, director of the Regional Program for Political Parties and Democracy in Latin America at the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, explained to Expediente Público that the CPAFFC is far from being an independent civil society organization, as it claims to be.

Suhr reiterated that the Association is directly controlled by the CCP and is part of the so-called United Front Strategy, «a central instrument through which China seeks to exert targeted influence on foreign actors, especially local politicians, city associations, and civil society organizations.»

The term «friendship» often masks the intention to exert political influence and underlying strategic interests, Suhr said.

In context: China accumulates ports in Latin America and the Caribbean

Trips and invitations

Neither the Association nor the Chinese media provided details of the signatories to the declaration. In addition, parallel to the Forum, 26 deputies from all factions of the Honduran Congress left for Beijing on a three-day tour with expenses paid by China.

The National Party distanced itself and announced in a press release on September 9 that the trip by its deputies was personal, «without the endorsement or representation of the party.»

Officially, the National Party argued that the deputies would attend a seminar on Chinese modernization at the Ministry of Commerce and exchange legislative and governance experiences with the CCP.

The CCP also invited operators from Nicaragua’s Sandinista regime on a parallel tour in September, announcing that it had sent some 20 officials and activists on a 15-day exchange.

Most notable was the participation of First Police Commissioner Francisco Díaz and Army Chief Julio Avilés in the 12th Xiangshan Forum, the annual conference on security and defense. Avilés also participated in the 6th China-Latin America (CELAC) Defense Forum.

These visits are taking place even though on September 5, the United States threatened visa restrictions on Central American citizens who collaborate with the CCP.

The first edition of the legislators’ forum in 2023, held in the city of Shenzhen, was attended by 30 deputies from 17 countries, including Ramón Barrios from Honduras, representing the ruling Libertad y Refundación (Libre) party, and Gonzalo Winter from Chile, representing Convergencia. The Chilean deputy was criticized for not reporting the trip to Congress and failed to mention it on his social media accounts, where he was very active.

A publication by the Chilean digital media outlet Ex Ante explained that these invitations usually come directly from the National People’s Congress of China, and that this year other deputies had their travel and accommodation paid for by China, equivalent to 9 million Chilean pesos each, or about $9,400 at the 2023 exchange rate.

Expediente Público wrote to the press office of the Free Party of Honduras to inquire about its participation in this or other forums in China but received no response.

Soft diplomacy narrative

Leland Lazarus, an expert on relations between China and Latin America, told Expediente Público that China’s soft diplomacy strategy is very similar to that of the United States, but obviously with its own objectives.

What China wants to project is that it is a developing country, like many other countries in the Global South. It presents itself as a country with no history of colonialism or imperialism, unlike the United States or Europe, which makes it—according to its narrative—a more reliable partner.

«China claims that it does not seek to impose its model, but simply to promote what it calls the ‘community of shared destiny’ (mingyun gongtongti in Mandarin),» Lazarus adds.

This idea proposes that all countries in the world, large or small, be treated equally, respect each other, and not interfere in each other’s internal affairs.

«This is one of the key messages that China wants to spread. Whether these messages are true or not is, of course, something we should debate, but that is the discourse it seeks to expand,» he said.

Also: Evan Ellis: China’s advance in Central America challenges the US

Working with elites

In the case of Central America, China’s use of soft diplomacy consists, above all, of economic incentives for elites and the propagation of its narratives, explained César Santos, a researcher at Expediente Abierto.

China also utilizes soft diplomacy between peoples, which seeks to influence academic sectors, civil society organizations, think tanks, journalism, and political parties.

This type of diplomacy, unlike high-level diplomacy between officials or within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative, «allows China to position itself as an important player in public debate, in the field of ideas, and in the discursive struggle between the West and the so-called Chinese model,» added Santos.

The Belt and Road is a program that began in 2013. It is a commercial connectivity project through investments in the strategic global infrastructure, such as ports and roads.

For its part, China’s «soft» instruments include direct or in-kind economic gifts through non-reimbursable cooperation. The Expediente Abierto academic said that there are also parliamentary friendship groups, as well as civil associations of friendship with China, comprised of local people who promote Chinese culture and Mandarin in their countries.

However, these groups and individuals also serve political objectives, as they are often directly linked to Chinese embassies.

Another important element is diplomacy between political parties, through the CCP’s International Liaison Department.

This form of diplomacy operates even in countries without official relations, utilizing local parties to train and indoctrinate party cadres, offer them trips—as well as journalists and academics—and create long-term networks with potential future leaders, Santos said.

Financing or buying?

China invests in financially struggling media outlets, establishes cooperation agreements, and guarantees the publication of favorable news, Lazarus said.

In the Caribbean, for example, he learned of media outlets with limited resources that went from asking for support from the United States to receiving funding from the Chinese Embassy. Since then, the media outlets have regularly published positive content about the Beijing regime.

One type of guest favored by China is journalists. Press trips showcase the most developed cities, hiding inequalities or internal problems, Lazarus emphasized.

On the other hand, there are Confucius Institutes that promote the learning of the Chinese language, culture, and diaspora. They seek to co-opt community leaders in different countries to align them with Beijing’s interests.

In some cases, these networks are also intertwined with organized crime, raising questions about the extent to which the Chinese government is aware of or tolerates these connections, Lazarus warned.

Read also: China tests democracy in Latin America

America on China’s radar

Yang Wanming is a high-level Chinese diplomat and currently the president of the CPAFFC. He took office in August 2023, replacing Lin Songtian, an expert on Africa.

The appointment is no coincidence. Yang has spent his entire diplomatic career in the Western Hemisphere since the 1990s, when he joined the Latin American and Caribbean Affairs Department of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where he became director in 2007. He then served as ambassador to Argentina, Brazil, and Chile.

«The Legislative Forum is not a neutral space for parliamentary dialogue, but rather an instrument for spreading Chinese narratives, such as the community of shared destiny for mankind or the multipolar world order,» Suhr said.

Participants are deliberately selected to show sympathy for China’s foreign policy positions, while critical voices are systematically excluded.

The forum is part of a comprehensive «soft power» strategy, Suhr argued, which is not based on mutual understanding, «but on targeted influence over foreign discourse: subtle in form, but unambiguous in its geopolitical objective.»

Subtle, but not harmless

«I know Latin Americans who were invited to China and later said that the attempts to influence them were superficial, but in the end, soft power not only requires money, but also time and genuine mutual interest to be successful,» Suhr said. However, such initiatives pose risks for the region.

China has used it to establish diplomatic relations in Central America, from Costa Rica in 2007 to Honduras and Nicaragua a couple of years ago.

César Santos explains that this is presented as development aid—infrastructure, scholarships, educational programs. As for specific incentives for elites, there is non-reimbursable cooperation, but in practice it entails giving bribes.

«While promoting language or culture can be considered legitimate soft diplomacy, exchange programs with legislators can facilitate corruption, political co-optation, and interference in domestic politics,» said Leland Lazarus.

Events such as Panama’s shift toward recognizing China under the government of Juan Carlos Varela (2014-2019) show how these dynamics can translate into concrete diplomatic and economic decisions, he explained.

Some investigations by Expediente Abierto reveal the hidden interests behind these seemingly harmless approaches and exchanges.

The Expediente Público report, China’s strategy to capture elites and its impact on Argentina, prepared by Latin American policy expert Constanza Mazzina, shows how the Asian nation managed to twist the arm of President Javier Milei.

Narrative and realities

After campaigning on the promise that he would not negotiate with communists, with the need for money and investment, «the renewal of the Chinese swap was necessary for the government’s economic security, and his change in discourse was focused on achieving that renewal,» Mazzina describes.

China’s strategy in Argentina consists of establishing long-term relationships. It is not only about economic ties with strategic investments, financing, and agreements; diplomacy also plays an important role.

Mazzina explains in his report that this diplomacy is «aimed at establishing personal ties with local officials and leaders, and with cultural and educational initiatives that seek to promote a positive image.»

Under this strategy, China has managed to cultivate a positive image in the local media, with celebratory articles by academics, and establish notable links with the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), the main state research center.

The study also notes that China secured lithium concessions with the support of the local government of Jujuy, as part of an aggressive strategy of direct engagement in the provinces, and even gained allies in anti-communist parties such as Propuesta Republicana (PRO) and La Libertad Avanza.

Authoritarian opportunism

The illiberal left in the region sees China as an alternative model of democracy and development, in which human rights can be subordinated to economic growth, Santos stressed.

Some also accept Chinese invitations out of ignorance, without really knowing how the Chinese system works, he added. Santos gave examples of institutions close to China, such as the National Liberation Party in Costa Rica, the Farabundo Martí Party in El Salvador, Sandinismo in Nicaragua, and the Democratic Revolutionary Party in Panama.

Some new right-wing parties, such as Nuevas Ideas in El Salvador, also share anti-Western rhetoric and see the Chinese model as an example of a democracy that is different from liberal democracy, more focused on electoral majoritarianism and with fewer institutional controls.

Latent risks

For Santos, the main risk of these trips and this diplomacy is not only soft influence, but what is called sharp power: it is not just a matter of persuading, but of eroding liberal democracies by promoting other concepts of politics and power.

China seeks to form networks of influence with legislators, journalists, and opinion leaders who spread the Chinese model and support decisions that are far removed from the rule of law.

The risk is normative. Santos explains: «For those of us who value liberal democracy and institutional checks and balances, this model is problematic because it places economic development above political freedoms.»

Interference and double standards

Lazarus recalled that China’s 2025-2027 action plan with the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) envisages inviting some 300 Latin American politicians per year—legislators, mayors, officials—totaling 900 over that period.

«This is happening just before important election cycles in the region, suggesting an attempt to influence potential presidential candidates before they begin their campaigns,» he emphasized.

Indeed, twelve presidential or general elections will be held on the subcontinent over the next three years, including the recent elections in Ecuador, whose second round took place on April 13.

Now, how does this cooperation differ from that of the West, such as Europe or the United States?

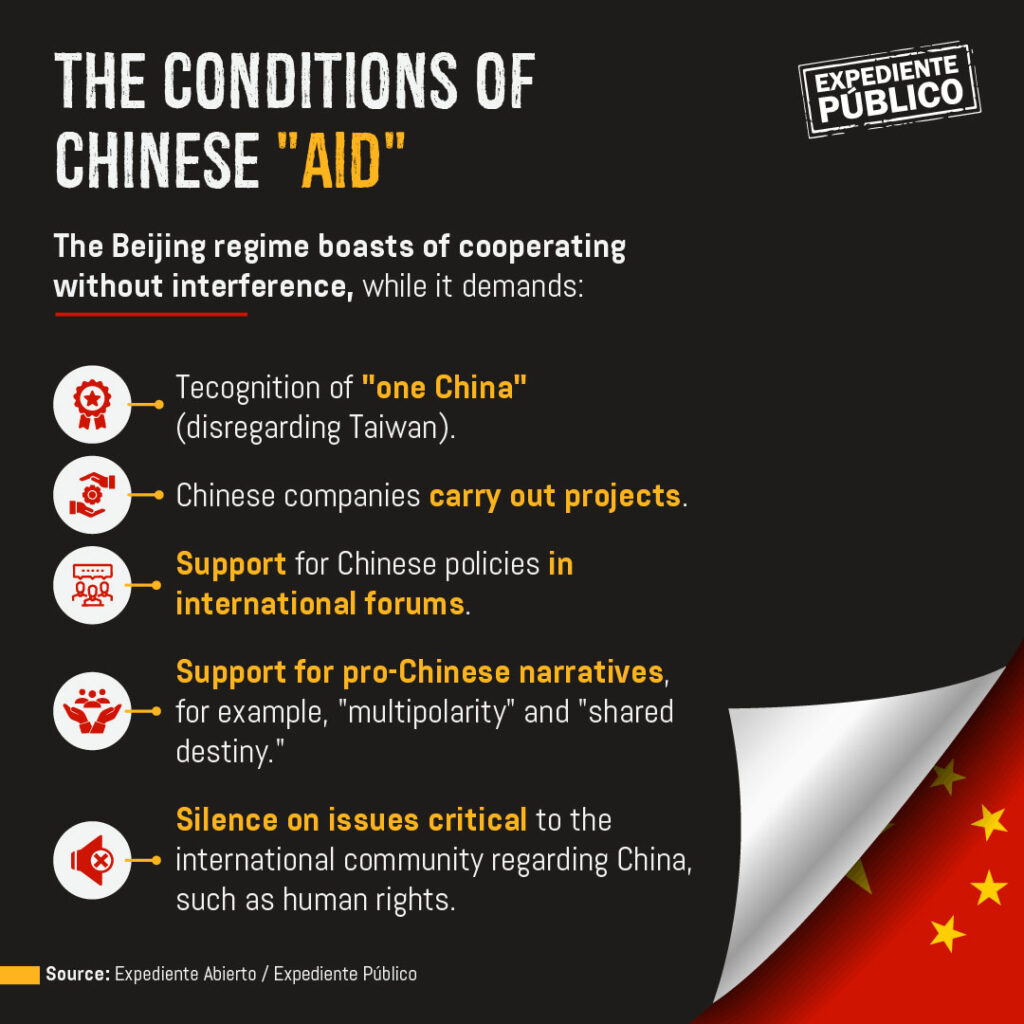

«Western international cooperation usually has democratic political conditionality. That is, it is distributed among countries that share democratic institutions and values, or seeks to promote democratization,» argued Santos.

In contrast, China presents its cooperation as «without political conditions,» claiming that it does not promote or impose values. But in practice, the opposite is true: there are conditions, albeit not democratic.

The researcher highlights that Chinese interference requires countries to recognize the «one China» principle in order to receive cooperation, in addition to condition projects through its state-owned companies, which also strengthens its agenda in international organizations on issues such as Taiwan, Xinjiang, or Tibet.

Accountability and transparency

Santos says there is evidence of paid trips that have led to opaque contract awards, such as in Panama with the fourth bridge over the Canal.

In response to this, Santos pointed out that civil society and investigative journalism are essential. He stressed the need to identify Chinese-funded media outlets that spread China’s narrative and to strengthen independent initiatives that can counteract this influence.

The academic added that political parties should also adopt a critical view, since in countries such as Panama and Costa Rica, most political forces show favorable positions toward China without considering the risks of linking themselves to a single party.

«Ultimately, the work begins with civil society, but it also requires democratic education aimed at political elites, so that they understand the differences between engaging with democracies and with a party-state like China,» Santos said.

Lazarus also stressed that several Latin American leaders are quick to criticize the United States for alleged interference in their domestic politics but are not so quick to criticize China.

If the priority is to defend the sovereignty of any country, then the interference of any power must be monitored, not just that of the United States, Lazarus argued.

According to the academic, «turning a blind eye to what China is doing makes no sense. That is why I believe that Latin American countries should increase their vigilance over its actions.»