*Other mechanisms for citizen participation, such as the Communal Councils in Venezuela, the Popular Councils in Cuba, and the Councils for Citizen Power in Nicaragua, all countries of leftist ideology, work as transmission lines to the Libre Party of the Honduran government.

** “In the case of Honduras, I would ready the alarm bells rather than the benefit of the doubt,” political scientist and Cuban historian commented regarding the Law on the National Roundtable for Citizen Participation proposed by the government of Xiomara Castro.

Expediente Público

For the historian and Cuban political scientist, Armando Chaguaceda, “Central America is currently living through a process of accelerated democratic backsliding occurring in democracies of different ideological affiliations, such as Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala.” In his opinion, the Law on the National Roundtable for Citizen Participation, which the government of President Xiomara Castro sent to the National Congress for approval, should be reason for sounding the alarm bells.

“In the case of Honduras, I would have alarm bells ready rather than the benefit of the doubt on standby,” Chaguaceda said in an interview with Expediente Público, where he analyzed the similarities between the Communal Councils in Venezuela, the Popular Councils in Cuba, and the Councils for Citizen Power in Nicaragua, all countries with which Castro identifies ideologically.

One of the similarities between these countries is that the models for citizen participation are focused not on empowerment or autonomy but ‘participacionismo’ and where citizens are not recognized as actors in a pluralist system.

Radical ideologies

The law does not promote “autonomous participation and but rather, a consultation mechanism, where the mechanisms for participation, which we have defined as local assemblies, are turned into transmission lines through which the governing party gives orders, mobilizes, and distributes resources,” the political scientist based in Mexico explains.

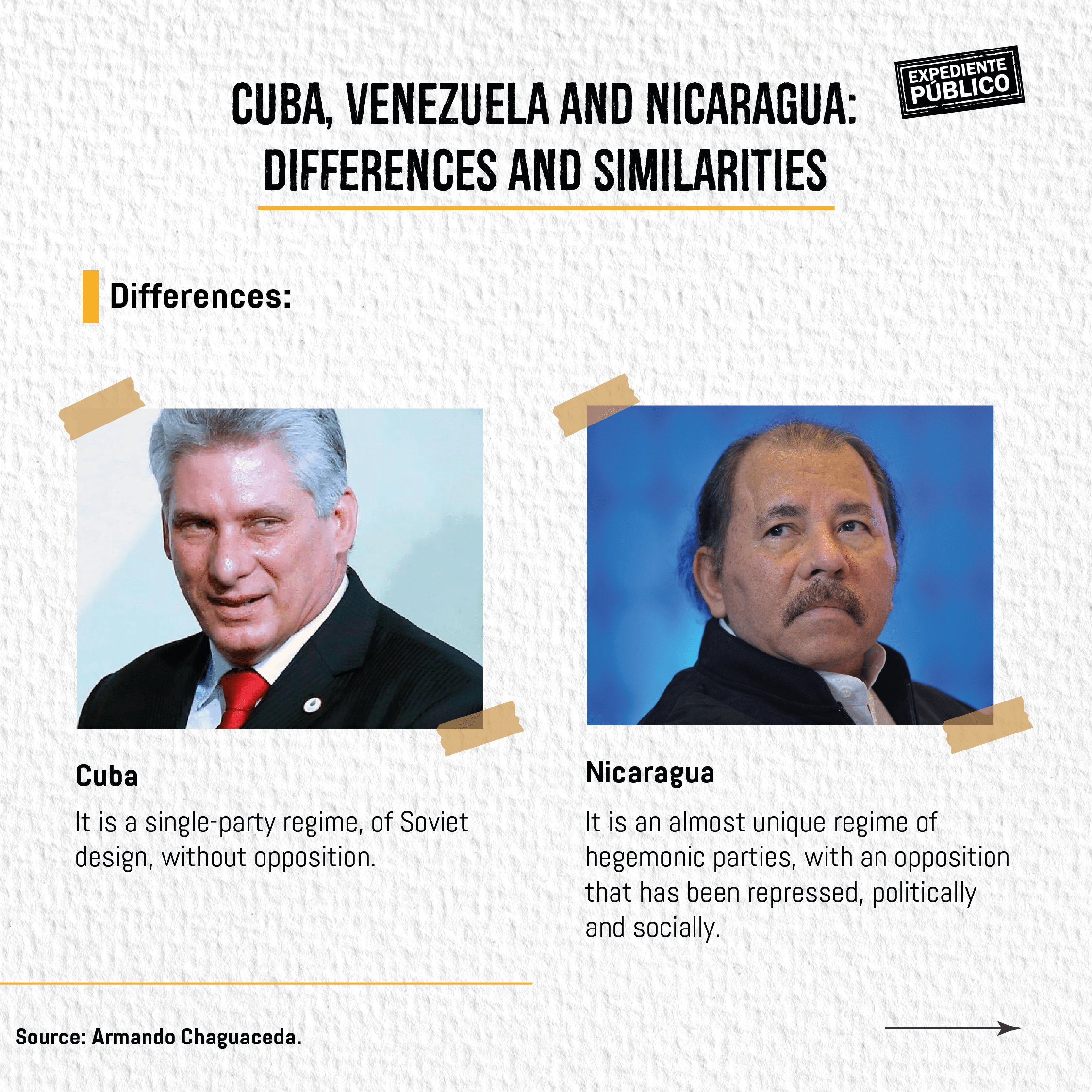

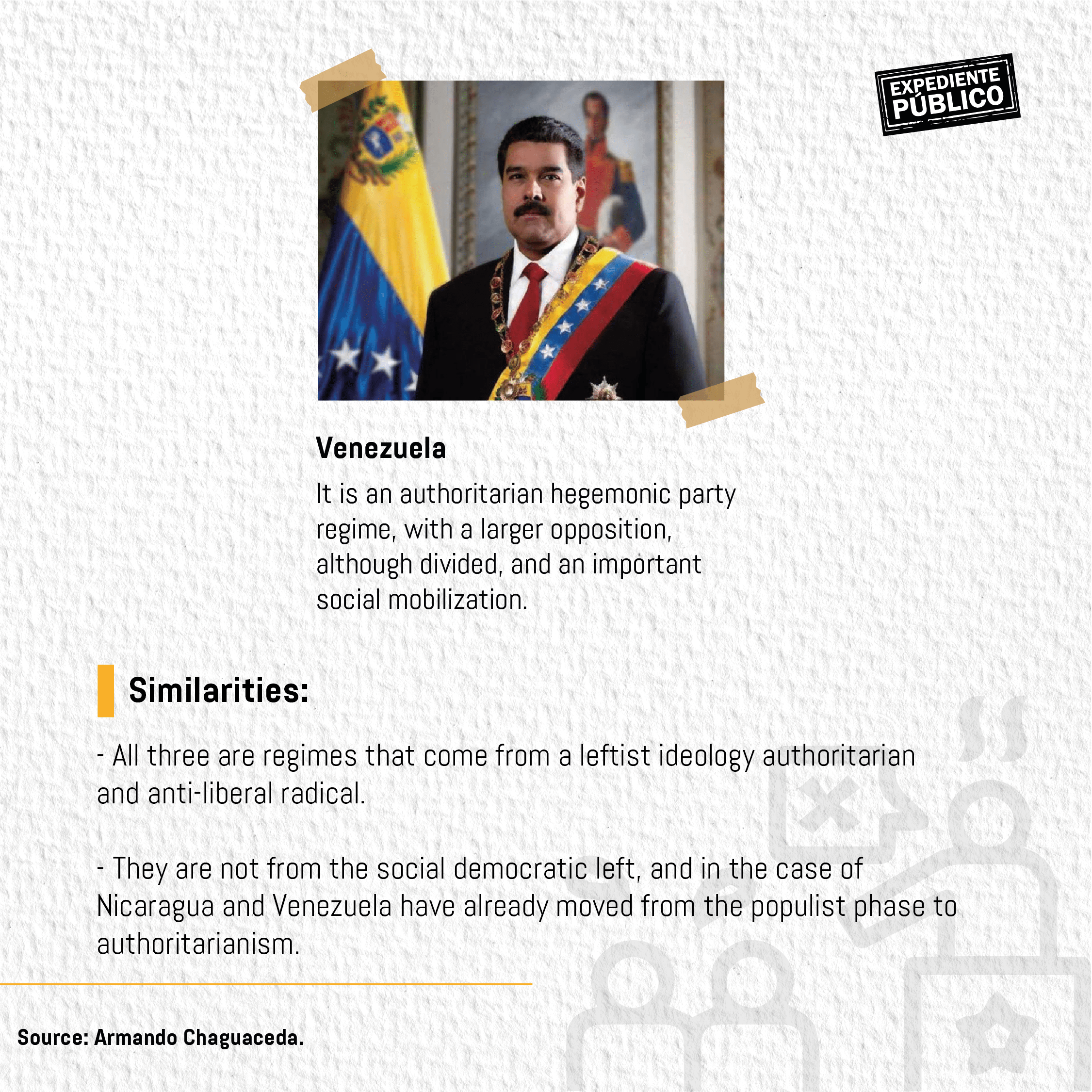

Chaguaceda explains that these countries have three different structures and evolution processes. Cuba has a hegemonic party system of soviet design, where the political opposition is not recognized by the government. Nicaragua also has a hegemonic party system, with essentially one political party for all practical purposes but where repression of the political opposition has existed. Lastly, the Venezuelan government is an authoritarian regime with a large yet divided opposition, where significant social movement continues to occur.

“But there are elements in common: the three regimes come from a radical, authoritarian, leftist, and anti-liberal ideology. They do not form a social democratic left; Venezuela and Nicaragua are not even populist governments, as they have already passed that phase. The governments are now clearly authoritarian,” he said.

Read: Honduras se vuelve cómplice de Rusia y Nicaragua

Espionage and mechanisms of control

These citizen councils, as extensions of the control apparatus of the State and the ruling party, “can also perform espionage or other mechanisms of control on those who dissent,” he said.

If there is still an opposition that is legal and alive, whether at the community or institutional level, “these mechanisms could work at the neighborhood level,” he continued.

On the other hand, in a country with a consolidated dictatorship, where the political opposition and civil society are suppressed, citizen councils serve to maintain the State’s control.

He recalled that when the government created the CPCs in Nicaragua beginning in 2007, the State did so based on “the previous institutions of liberal democracy, a participatory and consultation model open to a plural civil society and other types of actors.”

But the government substituted the former structure for the current one and subordinated the mechanisms for participation to the ruling party and the State, from the grassroots level to the top of the hierarchy.

Read: La justicia internacional persigue los crímenes de Ortega y Murillo

Representative and participatory democracies

“The participatory and/or direct democracy is a form of democratic governance that coexists with representation; it does not substitute it,” explained Chaguaceda.

Representative democracy assumes that citizens elect a representative, and participatory democracy is a space for citizens to become involved in certain instances, such as citizen councils that exist in Latin America, the US, and Europe.

Citizen councils are not at “odds with representative democracy, voting, or having a pluralistic system of parties and elected representatives. What is at odds with democracies are the governmental structures that discourage a diverse civil society,” he said.

This happens when the instances for citizen participation are subordinated to the executive branch, which can choose whether to active them. Other practices related to the use of city councils that discourage a diverse civil society include limiting council participation to political sympathizers, providing government resources only to those who are connected to the State in some way, and preventing the assembly of opposing groups that are not pro-government.

Chaguaceda also said to pay close attention to the government’s discourse. “If there is an attack on representative democracy under the pretext that participatory democracy is the only possible democracy; if the government is using a populist discourse to attack pluralism, political parties, and civil society; and if citizens are referred to as a homogeneous group of people, instead of recognizing the diverse population of Honduras; I believe that there are signs of a ‘participacionista’ attempt to undermine and manipulate the democratic system,” he warned.

The Honduran proposal

The Law on the National Roundtable for Citizen Participation, which was proposed by the executive branch and currently presented before the National Congress, seeks to eliminate the Forum for National Convergence (FONAC), which was created in 1994 as a national forum for dialogue but that has been used by the Juan Orlando Hernández administration to endorse acts of corruption such as that of the mobile hospital scandal.

The FONAC receives a budget from the State, and its executive secretary is appointed by the president of Honduras, who in turn, convenes the assemblies, which may also be convoked by more than half of the forum’s member organizations.

The new law, which consists of nine articles, proposes that the expenses be covered by the recently created Secretary of Strategic Planning, who will be the coordinator of the National Roundtable and through whom Castro will summon the participating organizations.

In other words, the new law prolongs the existing vertical hierarchy within the new mechanisms for citizen participation.

For Chaguaceda, the fact that this new mechanism will not manage its own funding or salaries means that it could be used as a double-edged sword. The roundtables could be used as a way of disincentivizing participation in certain cases “where members of social organizations [in poor communities] devote a decent amount of energy to surviving on a day-to-day basis,” because “creating ad honorem spaces would keep them from participating.”

Hypothetically, “if I cannot pay anyone to work but can illegally take money from other sources to have my supporters be able to work, these spaces of political participation and incidence can become a place where the government hires loyal followers without being adequately audited,” he said.

A third scenario is that nefarious logics may be incentivized, for example, in participatory spaces for consultation open to the business sector. These business groups can allocate more resources and free time to participate in the social organizations, which could cause them to be overrepresented in the councils to the detriment of societal sectors that seek representation through these mechanisms.

Manipulated spaces

Democratic mechanisms for direct participation, consultations, and civil society-State linkages appeared in Central American during the 80s and 90s as part of a global tendency toward similar participatory instruments and processes, according to Chaguaceda.

These instruments “came with the promise of broadening inclusion in a region torn by civil wars and serious problems of poverty, inequality, deficits in civil society, and state capture by traditional elites.”

Some worked better and were more open than others and implemented, for example, an agenda to promote transparency, decentralization of power, and accountability. Others, however, were empty, bureaucratic shells that have not solved anything, he said.

The Ley on the National Roundtable for Citizen Participation is “vague and generic” in that it “basically uses a rhetoric to empower the government while presenting itself as a space open to different societal actors.” In principle, this is not necessary negative as “the spaces could allow for consultation, instead of participation.”

Chaguaceda considers it important to view each one of the measures of the initiative for citizen participation within a political framework. The bill should be carefully evaluated if it is an exclusive initiative of the national government, if it has strong presidential bias in its content, and if, for example, the model that it replaces was more pluralistic or open because of who could convene the dialogues, who participated, and the ideas discussed.”

Positive experiences in the region

Chaguaceda continued by saying that “if the initiative goes together with any attempt to reconstruct and format the political regime by means of a Constituent Assembly, it should be reevaluated. Similar phenomena have occurred in other countries, where Constituent Assemblies have been spaces used by the government to manipulate citizen participation through an overrepresentation of the ruling party and changing the rules and design of the political process. The Andean Bolivarian experience is an example of this.”

He said that it is necessary to evaluate the participatory mechanism “if a call to citizens of this nature works together with a government that wants to strengthen its political position through a Constituent Assembly to reconstruct the political system, if the ruling party has populist traditions or ties with clientelism, or if its leadership has promoted populist rhetoric and actions.”

Read: Blinken y Nichols comprometidos en apoyar el retorno a la democracia en Nicaragua, Venezuela y Cuba

Chaguaceda expanded on this idea by saying that there are positive experiences of direct and participatory democracies in Latin America, which oppose populist and authoritarian ‘participacionismo.’ Such are the cases of Uruguay, Chile, Brazil, Costa Rica, and Colombia, where “for example, the participatory mechanisms cannot be convened by the president, the governor, or the mayor” but rather, by citizens, to guarantee pluralism and a diverse civil society.

Looking at regional experiences

Before the concerns generated by the new law on citizen participation, the Cuban political scientist indicated that it was necessary to evaluate who was promoting the legal instrument and the context under which the law was proposed to Congress.

Although the idea that “representative democracy is made up of corrupt elites that do not represent the population but rather, the towns that the politicians hail and that they hope to empower” is persuasive, the reality is that “you also do not empower citizens by creating participatory instances completely dependent on the political, legal, administrative, and economic power of the State,” he said.

He insisted that political actors and all Honduran civil society “look to regional experiences to see where there have been similar practices, which of these practices had authoritarian outcomes, which actors were protagonists when democracy survived or improved, and who were the main players when democracy experienced backsliding or degradation.”

He also said that it is important to point out that while “not all participatory democracy is ‘nothing but populism,’ ignoring the fact that participatory democracy has also played a role populism and authoritarianism in Latin America” would also be an error.

In his opinion, there must be an analysis based on evidence. “Ordinary citizens, not just the political class, should discuss this soon and question the government with arguments based on very clear elements.”

For Chaguaceda, “in politics, neither excessive indulgence nor excessive hysteria is helpful. Citizen participation is too serious and important to be dismissed as a synonym for populism. However, mechanisms for citizen participation should also be recognized as having been used by governments as instruments of manipulation.”