* A diagnosis of the causes of migration in this Central American country shows that Salvadorans continue to flee for the same structural reasons as always: security and economic crisis.

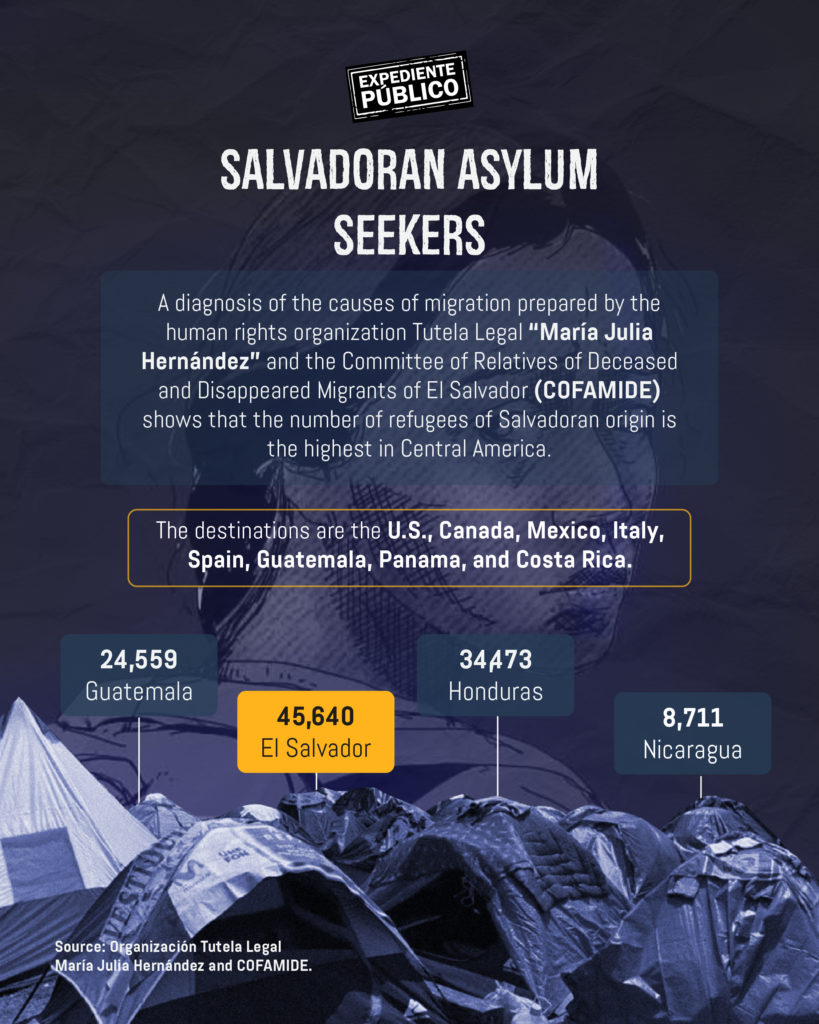

** Salvadorans rank first among asylum seekers in proportion to the rest of Central America.

*** Mexico received a total of 7,798 asylum requests in 2022, which is triple the number in 2021 when there were almost two thousand applications.

Eric Lemus / Expediente Público

A study on migration commissioned by two humanitarian organizations finds that Salvadorans continue to leave the country for the same reasons as always: either fleeing violence or seeking to escape the economic crisis.

The research shows that, while the government of Nayib Bukele talks about reverse migration, that is, Salvadorans returning to the country, a total of 100,000 citizens leave this Central American country annually in search of the American dream.

The Committee of Relatives of Deceased and Disappeared Migrants of El Salvador (COFAMIDE, Comité de Familiares de Migrantes Fallecidos y Desaparecidos de El Salvador), together with the Human Rights Association “Tutela Legal Dr. María Julia Hernández,” highlight that the findings put on the agenda an issue that governments try to omit, as is the case of those disappeared by migration.

Subscribe to the Public Records newsletter and receive more information

Many fall by the wayside because they do not complete an unexpected and increasingly dangerous journey due to organized crime on Mexican soil. In August 2023, the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) remarked that “migrants and refugees are exposed to many dangers.”

“She never knew her father”

Twenty-two years ago, Telma Acevedo’s husband disappeared somewhere in southern Mexico on his way to the U.S. He left behind two daughters: a six-month-old and a two-year-old, and a distraught mother waiting for news.

Two people who were on the journey and were deported told her they saw him in Chiapas and then in Oaxaca before going their separate ways.

Two decades later, Telma, who is one of the pioneers of COFAMIDE, is still searching for any sign of the last trace of her husband, William Gustavo Pérez.

“My youngest daughter is the age of how long he has been missing. She never knew her father,” says to Expediente Abierto the woman who founded this organization in 2006 along with other mothers, wives and relatives who do not rest in finding their migrants.

“We don’t talk about those who fell by the wayside, about the disappeared, we only talk about remittances, about those who did arrive and were successful,” she deplores.

Salvadorans in search of refuge

Some of the findings of the research that stand out is that the majority of Salvadorans who emigrate leave the country predominantly in January and that they continue to be the population with the highest request for refuge.

“It is classified as a transit country for irregular migration and as a country whose population emigrates mainly to the U.S., but also to Guatemala, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, Costa Rica and Panama,” Celia Medrano, the leader of the analysis, told reporters.

“In Mexico (in 2022), El Salvador ended up with 7,798 asylum requests” when in 2021 the registered applications were only almost two thousand, Medrano exemplified.

In November 2022, President Nayib Bukele celebrated that El Salvador was not included in the list of the top 10 countries with the highest irregular migratory flow to the U.S.

But the consultant explains that this happens as an effect of the increase in the migratory flow of other nationalities. “The data from other countries skyrocket, so, of course, El Salvador’s level drops percentage-wise,” Medrano warns.

“If we get out of the top 10 of migrants apprehended trying to cross the border, it has more to do with not because they have stopped leaving (…) but because the number of migrants has grown, for example from Nicaragua and Haiti to the United States,” she adds.

Relentlessly searching

Luis Alberto López, who is also a founding member of COFAMIDE, recalls that at the beginning the organization was born motivated mainly by the efforts of women, since those who migrated were generally the fathers of families.

However, patterns vary because due to structural violence and lack of employment in El Salvador, adolescents, unaccompanied children and women began to leave the country.

“I have been searching for my brother for 22 years and one of the difficulties to face is the indifference to the subject. In other words, the missing immigrant does not generate money. So, it didn’t matter at the time,” López told Expediente Público.

Luis’ brother left on February 26, 2001, fleeing unemployment. In that year, this Central American country suffered two earthquakes, on January 13 and February 13, which devastated the economy.

In context: Nicaragua, migración y crimen transnacional, esto es lo que preocupa a EEUU en Centroamérica

Luis remembers that his brother phoned the same day he left home to let him know that he was in the city of Tecún Umán, ready to cross into Mexico.

However, then came the news of a shipwreck where Luis Alberto’s brother was allegedly traveling with other migrants. When a humanitarian mission traveled to Chiapas in search of information, local authorities denied the existence of the incident.

A DNA bank

In 2010, the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF, Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense) sought out COFAMIDE to create a DNA bank and improve the search with scientific and accurate information.

The EAAF team, which is recognized for identifying the disappeared of the dictatorship in Argentina, contributed to the foundation of a genetic database with samples collected from relatives in Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Chiapas and the State of Mexico.

Thanks to the efforts made by COFAMIDE, in 2011 the government of former President Mauricio Funes approved a special law to address the problem and also created the National Council for the Protection and Development of Migrants and their Families (CONMIGRANTES).

“That’s where we tried to position the issue of the disappeared more. But, in this course there have been changes that unfortunately have come to throw away everything that we had worked on or to hinder it because they have made it difficult for us to continue positioning the issue,” explains López to Expediente Público.

Recently, on Wednesday, September 27, the Legislative Assembly, which is controlled by the governing party Nuevas Ideas (NI), dissolved CONMIGRANTES and transferred its powers to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, specifically to the Vice Ministry of Diaspora and Human Mobility.

Read furthermore: Migrantes salvadoreños, no todo es color de rosa en El Salvador de Nayib Bukele

The deputy of the Vamos party, Claudia Ortiz, criticized the measure because the Council’s budget goes to the General Budget of the Nation, in addition to the fact that it nullifies the presence of civil society.

“The dissolution of COMIGRANTES implies taking away spaces for participation from associations of Salvadorans living abroad, and the possibility of participating in the review and proposal of laws and public policies to address the issue of migration,” Ortiz said.

The Other Side of Migration

Omar Jarquín, COFAMIDE’s legal representative, insists that the organization’s job is to show the other side of migration.

“We have to see situations such as young people who leave with the illusion that they are going to lift their families out of poverty; but, in reality, they come back in a coffin. And that could have been avoided if they had had the conditions to forge a future in the country,” Jarquín told Expediente Público.

Jarquín lost his son David Alexander more than nine years ago when the young man arrived in Reynosa, on the U.S. border, and there was no further communication.

Also: Fin del Título 42: ¿Será esta medicina, peor que la enfermedad para detener la migración?

The activist, however, remains hopeful that regardless of the changes, “they will continue to work with the government in power because the Foreign Ministry is part of the forensic bank of missing migrants.” After the presentation of the study, the researcher in charge, Celia Medrano, said that one of the main difficulties in developing the diagnosis was the restriction on public information and statistics on irregular migration.

“The multicausality of the migration phenomenon cannot be addressed because people are never going to say the reason why they leave the country if they feel at risk in El Salvador.”

For his part, the coordinator of the Human Rights Association “Tutela Legal Dr. María Julia Hernández,” Ovidio Mauricio, told Expediente Público that the usefulness of the information obtained “allows us to understand the complexity of the phenomenon because El Salvador continues to be a country that expels its own population.”

During the week of October 16 to 20, 2023, the Jesuit Network with Migrants organized the academic colloquium “Free to choose whether to migrate or stay,” which was attended by Expediente Público.

Jesuit priest Rafael García, who presides over the Sacred Heart of Jesus parish in the city of El Paso, Texas, said that the flow of migrants has increased in recent years.

“The problem of migration lies in the countries of origin that are not generating better living conditions for the inhabitants,” said the religious leader. “It reflects humanity’s failure of political, economic and social systems.