Expediente Público

In November, in the midst of the global COVID-19 pandemic, Honduras will hold general elections to elect the country’s president, representatives and mayors. Conflict and danger are predicted for the election because it has started out without any agreement between the participating parties about a new Election Act that would have removed the specter of fraud and social upheaval that the country has experienced in recent years.

Some 14 political parties will participate in the November 28 elections, including the main political groups, Nacional (extreme right), Liberal (right) and Libre (left liberalism). In total, some 2,490 public positions will be up for vote, including that of president, three presidential appointees (vice-presidents), 298 mayors, 128 councilors and 20 seats in the Central American Parliament, which end their term in January 2025.

The University Institute on Democracy, Peace and Security (Iudpas in Spanish), of the National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH), has warned that for these elections “there is a high probability that the features of the 2017 electoral process will be repeated, when the weakness of the electoral institutions was clear, and the lack of confidence and credibility of the results brought a crisis of governability to the country and sowed confrontation in the post-election period, which still persists.”

One of the most worrying events recorded occurred on December 26, 2020, when four men wearing ski masks and black shirts murdered indigenous peasant leader Félix Vásquez, defender of the El Jilguero watershed and candidate for representative of the opposition party Libertad y Refundación (Free). It was not until January 23, 2021 that a person allegedly involved in the incident was arrested. “Societal violence and criminal violence blend into political violence. It is a mixture, but political violence must be interpreted in a broader sense and within that perspective it is likely that we will have high levels of political violence this year,” sociologist Eugenio Sosa, a social science professor at UNAH, predicted to Expediente Público.

Read also: A 2021 election with a cautious forecast in Honduras

Sosa added that “this trend is foreseeable in a context where social and economic problems are combined with impotence and public despair. The government and its institutions are part of a corrupt system that operates both centrally and in the territories, where a very serious militarization is taking place, both of official forces and criminal groups.”

An analysis of the last two elections in Honduras, in 2013 and 2017, shows that both were conflict-ridden but the most concerning aspect is that the violence showed an upward trend. For example, the number of victims increased by 4.2%, from 48 around the 2013 primary and general elections to 50 in 2017. The victims were from a variety of political orientations, but for the most part they were opponents of the ruling party, the Nacional party.

Sociologist and former university rector Julieta Castellanos highlighted that election violence in Honduras is extremely complex due to the variety of interests involved, including organized crime, which is fighting to control strategic areas, both rural and urban.

In an interview with Expediente Público, Castellanos, author of several books and essays on politics, development, corruption and transparency, recalled that in the case of the 2017 election violence, more victims were claimed after the elections, when thousands of people carried out numerous protests, alleging that the Nacional party’s win was fraudulent.

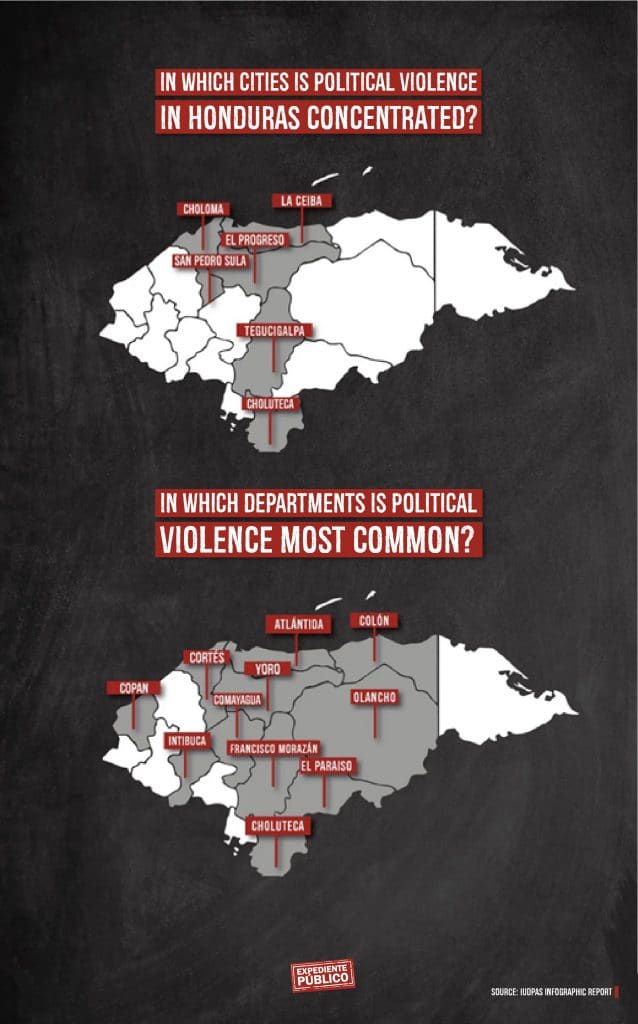

The Report on conflict and political violence in the 2016 and 2017 general and primary elections prepared by Iudpas confirms that the violent events around these two elections took place before, during and after election day. The investigation showed that of the country’s 18 departments, 10 were affected. The northern and central areas reported the highest number of fatalities. The department of Cortés had 36% (18) deaths, Atlántida 18% (9), and Francisco Morazán and Yoro had seven and six victims, respectively.

Political violence is concentrated in fewer than 10% of the country’s 298 municipalities and in 60% of its 18 departments. According to these data, the most dangerous places may be the city-municipalities of San Pedro Sula, Tegucigalpa, El Progreso, La Ceiba, Choloma and Choluteca. Among the most insecure departments are Cortés, Francisco Morazán, Yoro, Atlántida, Colón, Choluteca, Copán, Intibucá, El Paraíso, Olancho and Comayagua.

According to the 2013 Iudpas Report, during the election process three mayoral candidates were assassinated, one acting mayor, two vice mayors, two councilors in the performance of their duties, two candidates for councilors, 18 party leaders and activists, one deputy and six relatives of candidates for elected positions. In total, 35 homicides of candidates and officials were registered, triple the number recorded in the 2012 primary elections, when there were 13 homicides of candidates for elected positions.

Economic decline

Fourteen political parties are registered for the November 28 elections, and some 2,490 public positions will be contested, including president of the country, three presidential appointees (vice-presidents), 298 mayors, 128 councilors and 20 seats in the Central American Parliament, who will end their term in January 2025.

The factors that could lead to a violent political scenario include deterioration of the economy; increased migration; constant corruption scandals; environmental conflict; high levels of violence and insecurity; and the government’s difficulty in managing the coronavirus crisis that has left more than 3,000 dead and 200,000 cases in the country, as well as the tropical storms Eta and Iota in 2020, which affected thousands of people, leaving economic losses on the order of 1.8 billion dollars, according to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, (ECLAC).

The Honduran economy, with four out of every ten people unable to afford even one meal a day, fell by as much as 10.5% after the passage of hurricanes Eta and Iota, to which has been added the pandemic. According to calculations, this year at least 71% of the population is in a state of poverty increasingly close to extreme, and between 500 thousand and one million are newly unemployed.

You may be interested in: Political violence in the 2021 Honduran elections

Millions lost to corruption

The Social Forum of External Debt and Development of Honduras (Fosdeh in Spanish) estimates that in 2014 and 2018, corruption cost Honduras about 10 billion dollars, an amount equal to 10% and 12.5% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) in those two years.

The director of Fosdeh, economist Mauricio Díaz Burdett, stated that organized crime, the private sector and the public sector are the spheres that account for “more than 90 percent of the destination or illegal appropriation of resources” from bribes, illegal fees, violation of the State Contracting Law, tax evasion and theft.

Between April and July 2020, the National Anticorruption Council (CNA) presented a series of eight reports entitled “Corruption in the time of COVID-19,” which revealed situations such as contractual breaches due to unfinished and poor quality construction projects, inconsistencies in the procurement processes for equipment and materials, strategic favoritism to benefit family members, advantageous conditions for supplier companies, and procurement processes not conducted according to the principles established by the State Contracting Law. However, these accusations do not seem to trouble the government of Juan Orlando Hernández or the Nacional party, which has been dismantling the few existing defenses against corruption, including elimination of its greatest “enemy,” the Mission of Support Against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (Maccih in Spanish), created in 2016 through an agreement between the government and the Organization of American States (OAS).

The investigation of a few corruption cases involving senior officials and parliamentarians sealed the fate of the Maccih. Its mandate was to be renewed in January 2020, but the Government did not agree, a move that was “tolerated” by the OAS General Secretariat, which did not put up much resistance.

In Honduras, not even those deprived of liberty are safe; more than 50 inmates were murdered in 2019 and 2020 in various prisons around the country, which remain overcrowded with some 22,000 inmates.

International organizations that work to support press freedom note that journalists and reporters are the target of systematic acts of violence and threats, perpetrated by both individuals and State agents. About twenty were killed between 2019 and 2020, with 91% of the cases protected by impunity.

Violence based on gender identity or sexual orientation is another priority challenge. Honduras does not have data on murders based on gender identity, but civilian sources estimate that around 325 members of the LGBTQ community were murdered between 2009 and 2019, to which can be added 20 more in 2020.

A similar situation occurs with women. The National Observatory of Violence (ONV), attached to Iudpas, reports that some 300 women were murdered in 2020, crimes which, according to feminist organizations, have 94% impunity.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the “culture of violence” in Honduras is considered to be a chronic epidemic. Homicides in the country are quadruple the rate of 10 murders per 100,000 inhabitants, which is the threshold to begin considering violence as an epidemic.

Year after year, the country continues to have a shocking homicide rate, despite the reduction in the average of these crimes in 2020. Official figures show that the country recorded 3,415 homicides as of December 26, which implies a daily average of 9.46. 2020 saw a more than 15% reduction in homicides over 2019, a decrease probably linked to the restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

The ghost of re-election

Since the overthrow of former Liberal President Manuel Zelaya Rosales in June 2009, Honduras has gone through several political crises. The most influential Nacional party figure in the past decade has been Juan Orlando Hernández, president of the country for two consecutive terms, 2014–2018 and 2018–2022. Since the formal return to constitutional order in 1982, he has been the only president who has been able to get re-elected, yet the country’s constitution prohibits re-election and even considers it “treason” to suggest it.

See also: Multiple crises, polarization and political violence threaten election year in Honduras

In the opinion of Joaquín Mejía, lawyer, academic and human rights defender, Hernández’s re-election “cannot be understood without the context of subordination and almost absolute control of democratic institutions by the Executive Power, from the Supreme Court of Justice, through the National Commissioner for Human Rights, the National Congress, the Public Ministry, to even the Armed Forces.

In these elections, the ruling party’s fear is that they might lose control of the public administration, especially if the potential winner of the November general elections is the Libertad y Refundación (Libre) party, founded and led by ousted president Zelaya Rosales, who they fear may be looking for revenge.

“The image that citizens have of State institutions, politicians and even the organisms of civil society itself is that they are closely associated with corruption and are easy victims and accomplices of the practices of organized crime and drug trafficking,” a November 2019 study by the Center for the Study of Democracy (Cespad) stressed.

Since the last primary and general elections in 2017 and up to the present, the socio-political situation, instead of improving, has seen a worsening trend. The nation is plagued by institutional weakness, lack of independence of the new National Election Council (CNE) and National Registry of Persons (RNP), deepened corruption, and organized crime infiltrating political campaigns by illegally financing the candidate lists. Citizens are fed up with politicians falling into disrepute.