*So far in 2022, the United States has solicited the extradition of seven Hondurans accused of drug trafficking. However, Honduras has no security strategy or law that regulates these extraditions.

Expediente Público

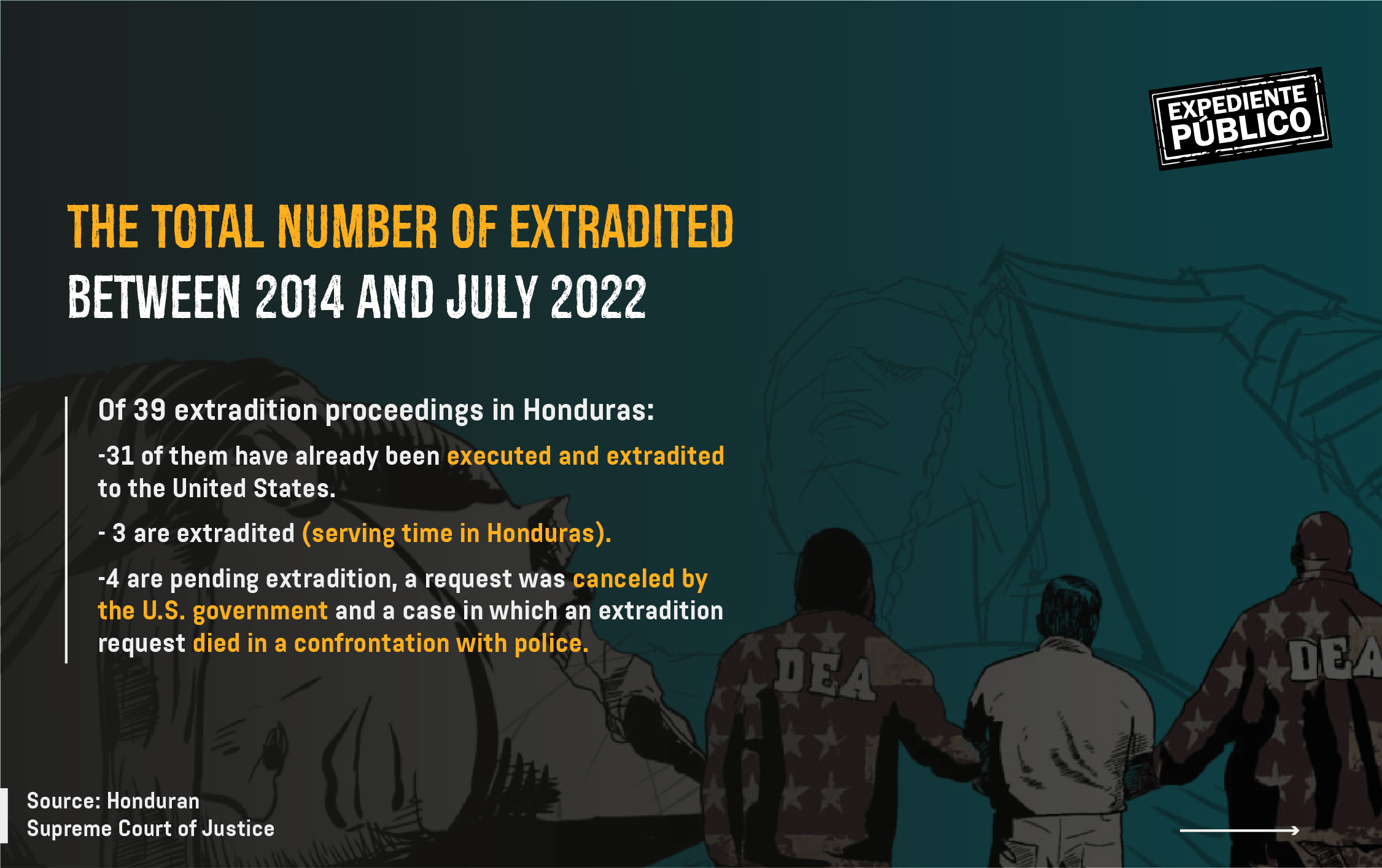

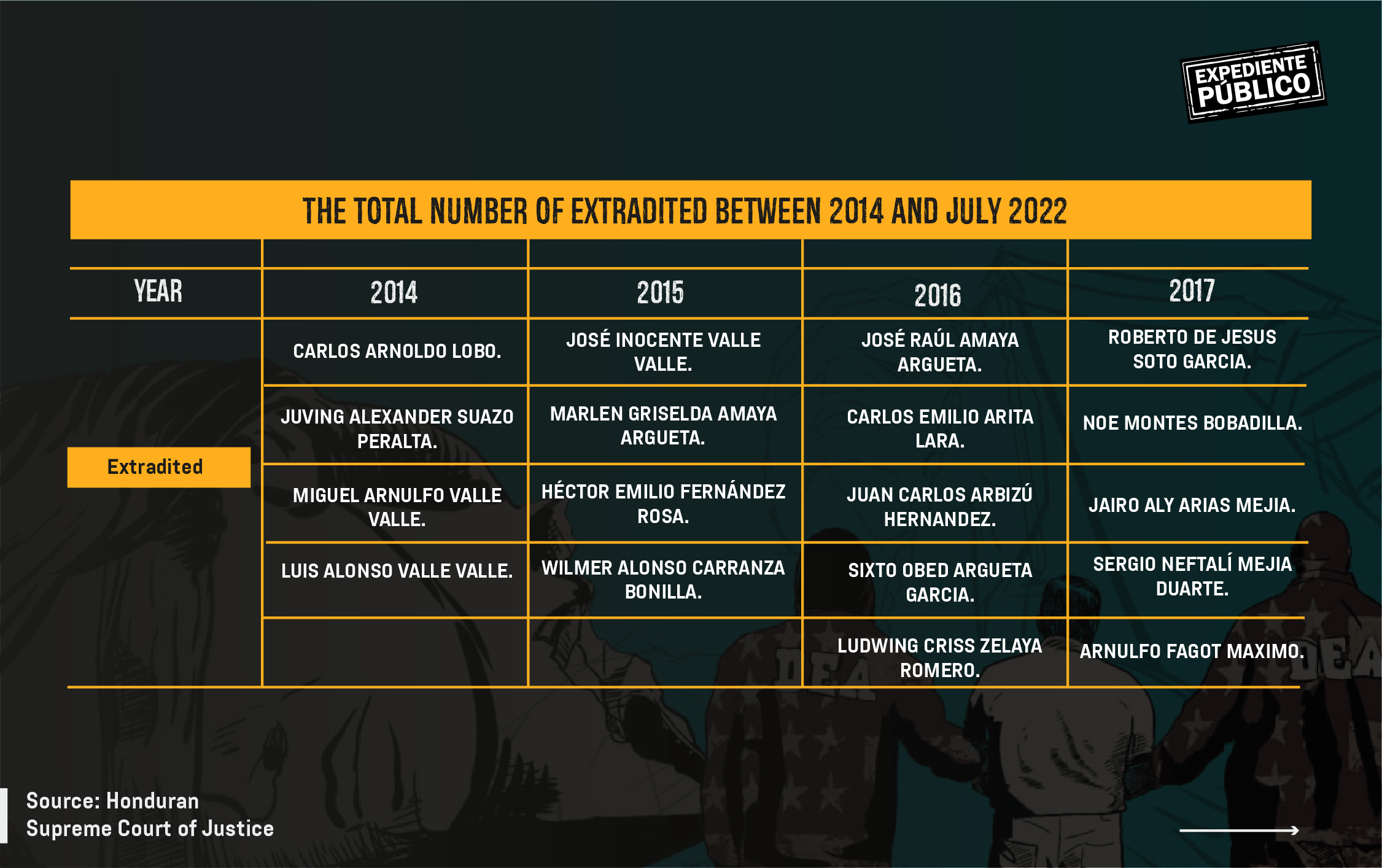

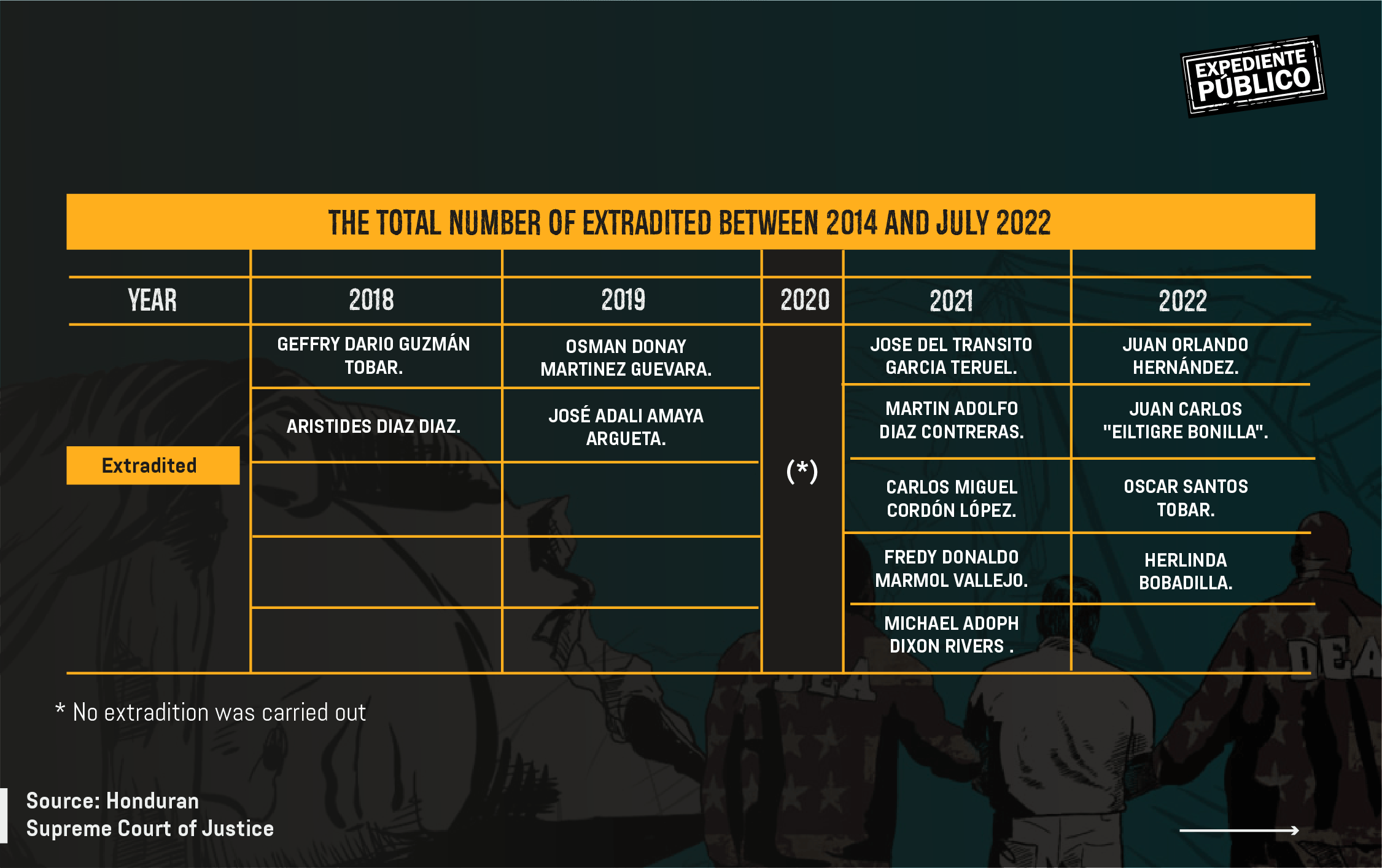

From 2014 to July 2022, the Honduran government has handed over a total of 31 Hondurans to the United States (US) under drug trafficking chargers. Under the Xiomara Castro administration, the US has extradited four Hondurans thus far. While some say that the fulfillment of extradition requests by the Honduran government speaks to a willingness to cooperate with the US, this cooperation also indicates a weak justice system.

Among figures for 2022 (Castro assumed the presidency on January 27, 2022), the arrests of former President Juan Orlando Hernández Alvarado and former National Police Director Juan Carlos “El Tigre” Bonilla are particularly worth highlighting.

Read: En enero de 2023 iniciará juicio de Juan Orlando Hernández en Estados Unidos

According to data from the Honduran Supreme Court of Justice, ten years after clearing the way for extradition in the country, the Honduran government has entered into 39 extradition proceedings with the US, with which Honduras has an agreement since 1909. However, the 1981 constituton prohibited the extradition of Hondurans, which created grounds for the document’s reform in 2012.

Extradition and cooperation with the US

According to data gathered by Expediente Público, the second highest number of arrests (six) of extraditable persons in Honduras has been reached thus far in 2022. With eight arrests, 2014 was the year with the most arrests of extraditable persons and the first time that extradition took place in the country.

This year, the government extradited four Hondurans to the US: Óscar Fernando Tobar (detained in 2021) and Herlinda Montes Bobadilla, in addition to Hernández Alvarado and “El Tigre” Bonilla. There are also three extradition processes pending, which would count toward the 2022 numbers. Aside from 2014, 2016, 2017, and 2021 saw the most extraditions in previous years, with the government seeing five cases per year.

Despite these figures, analysts interviewed by Expediente Público point out that it would be premature to consider this year as significant until those three extradition cases come to fruition, given that there is no major difference between the achievements of the Juan Orlando Hernández administration and the current government in this regard.

In an interview with Expediente Público, the Director of Policy and Strategic Initiatives for the Seattle International Foundation (SIF) Eric L. Olson said that to date, “the two governments of Hernández and Castro have utilized extradition as a tool for cooperation with the United States.” “The Juan Orlando government extradited many people to the United States. In this sense, it would be incorrect to say that his administration did not contribute as much to extraditions as the current government has,” he said.

Olson added that “for the United States, receiving lists of extraditable persons or persons solicited by the government for extradition is a positive sign.” He also recognized that relations between Honduras and the US go beyond extraditions, which has been confirmed by recent visits to Honduras by US government officials, due to a US interest in supporting the Central American country in different issue areas.

“But extraditions continue to be part of this positive moment [for US-Honduras relations],” he affirmed, despite the attitude of the Honduran government toward certain issues, such as President Castro’s absence during the Summit of the Americas, held between June 6 and 10, 2022, or the Honduran government’s decision to recognize, publicly, the Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega with an award.

This award was given to the Nicaraguan Ambassador Sidhartha Marín in Tegucigalpa, Honduras in June 2022 during the ceremony of the commemoration of the 13th anniversary of the Honduran coup d’état. The plaque recognizes the Nicaraguan government for “its support of democracy and Honduran resistance to the coup d’état in 2009 which overtook the democratic presidency of José Manuel Zelaya.” The award ceremony took place during a time when the Ortega regime had at least 190 political prisoners, had held elections without a legitimate electoral opposition, and had committed human rights abuses, generating an exodus of refugees from Nicaragua. As of May 2022, 142,702 Nicaraguans had solicited asylum in Costa Rica since the 2018 uprisings in Nicaragua. However, “there is still an opportunity or a window to build a positive relationship [between the two countries],” according to Olson.

Read: ¿Es Estados Unidos un aliado de la lucha anticorrupción en Honduras?

‘Narcos’ for the US; powerful people for Honduras

One of the conditions that Honduran laws impose so that the government can continue to process extraditions is that the person, of which extradition is solicited by the government, does not have any pending proceedings with the Honduran justice system. Some of those who are now incarcerated in the US prison system were prominent politicians in Honduras, such as former President Hernández and former Representative Fredy Nájera. Others had lower profiles but lived in huge mansions and drove luxury cars. Police officers and important farmers and businessmen are also of those imprisoned in the US. None of the incarcerated individuals who were extradited by the US had pending cases with the Honduran courts.

For Olson, this situation reveals the existence of certain difficulties in applying justice not only in Honduras but also in the rest of Central America, as “public prosecutors and Central American courts, while there are exceptions, have been affected by judicial manipulation, weak institutions, and low prosecutorial capacities.”

In Central America, “if the judicial system does not operate in an independent manner and lacks the capacity to affect the most powerful Hondurans, both politically and financially, justice will continue to depend on extradition to solve the region’s problems.” Olson suggests that “it would be better for Hondurans to face justice in Honduras, in the form of the legitimate and honest prosecution of corrupt officials and those who participate in organized crime, instead of the US’ having to extradite them.”

Olson adds that if he were to ask Hondurans on the street if they “trusted the courts or public prosecutors,” the population would respond negatively. In other words, Hondurans do not trust state institutions or accept judicial organisms in the country, which is debilitating to democracy in Honduras.”

Weak links

The Director of Justice and Security of the Association for a More Just Society (ASK) Kenneth Madrid recognizes that “Honduras has a weak justice system” and requires a different approach, beginning with “an adequate election of Supreme Court justices, which would need to be impartial and not politically charged.” Madrid insisted that the same conditions be required of the Public Prosecution Service.

Honduran analyst and attorney, Raúl Pineda suggested that “the idea is to have honest justices who are not influenced by organized crime, which has occurred previously in instances where organized criminal structures have invested large amounts of money into votes in favor of congressmen groomed by their people.”

The justices of the Honduran Supreme Court of Justice are elected by the National Congress, which gives the judicial institution political affiliation. Historically, the Supreme Court of Justice has been composed of justices affiliated with the Liberal and National parties, usually representing a ratio of eight to seven, with eight corresponding to the party in power. But in more recent years, political ties have also included organized crime links. At least two former congressmen, two former ministers, and a former president, Juan Orlando Hernández, have been indicted in US courts on drug trafficking charges. On July 18, 2022, the National Congress approved a new law to nominate judges to the Supreme Court of Justice; however, the law has received some backlash from critics who claim that it fails to prevent political influence on the courts.

Read: Honduras: Entre dudas y urgencias afinan nueva ley para elegir a magistrados de la Corte Suprema

A weak strategy

Representative of the ASJ, Madrid considers that “regarding extradition arrests, the justice system is doing its part for the moment.”

The attorney Kenneth Madrid added that it is important not to lose perspective, since extraditions are not defined as part of a national security strategy. “There is no document, no strategy that exists to incorporate an integrated work strategy into extradition matters. The government must comply with what the Constitution dictates and receiving governments request, in addition to following the legal procedures laid out by the Supreme Court of Justice.”

The attorney Oliver Erazo agrees that there is no strategy regarding extraditions; “extraditions are not a priority for the government because whoever is requested for extradition is extradited, which is not a coherent policy.”

Erazo told Expediente Público that it would have been ideal “to have an extradition law in place because without such a law, the plenary of the Supreme Court of Justice had to create a judicial order,” or a procedure that outlines the steps necessary for an effective extradition agreement.

Extradition in Honduras was no longer prohibited as of 2012, when the National Congress, led by Juan Orlando Hernández during the government of Porfirio Lobo Sosa, reformed Article 102 of the Constitution of the Republic. The crimes prosecuted are drug trafficking, money laundering, and terrorism.

No law to regulate extradition

An extradition law was never passed by Congress. Instead, the judicial process is allowed by means of an agreed-upon court order approved by a majority vote of the justices of the Supreme Court of Justice.

For Olson, “it would be positive” to have an extradition law, as part of the legal procedures and laws in the country. “While they are not carrying out extraditions in an extrajudicial manner and continue to respect legal procedure, having an extradition law in place would be positive and valuable [for the country].”

For attorney Pineda, the establishment of a law on extradition is imperative: “anything related to human rights, including the right to freedom, must be reflected in the law.” He also points out that caution should be exercised when formulating such a law because “it could eventually serve to complicate or delay extradition processes that, up to this point, have been quite fast and efficient.”

The main requirements for extradition are set forth by the Extradition Treaty between Honduras and the US, which outlines that crime(s) must have taken place within the jurisdiction of the requesting country and be punishable under the laws of both countries. According to a review of the extradition process, Honduras takes between three and four months, from the time the defendant is captured until he or she is in US custody, to complete extradition to the US.

The US Department of State sends an extradition request to the Honduran Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which sends the request to the Supreme Court. The justices designate a special judge to the case, who verifies that the documentation received by the court meets all requirements for extra. Based on previous cases, once the defendant stands before the Court, the judge informs him or her of the reasons for his or her arrest and sets a hearing at which extradition is granted.

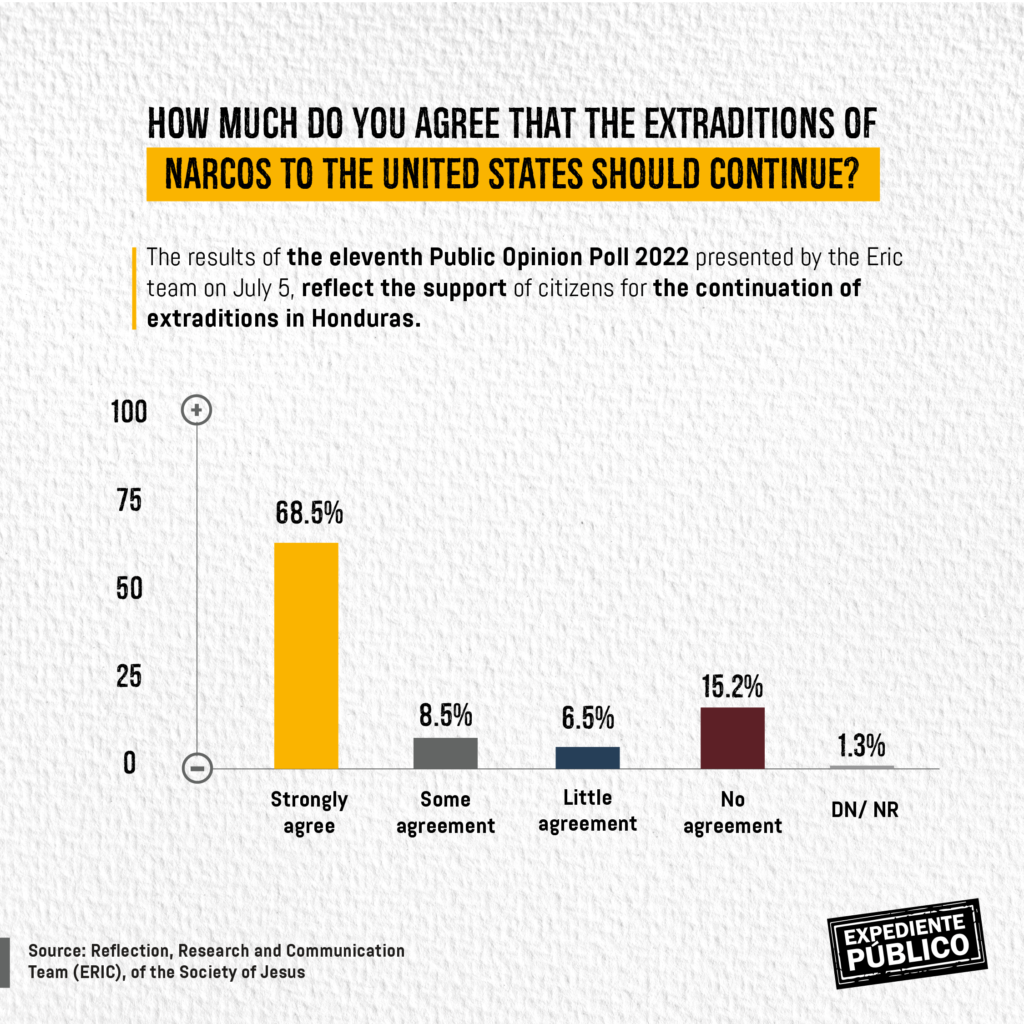

Extradition in Honduras has received overwhelming support from the general population. This support is reflected in a 2022 public opinion poll carried out by the Reflection, Research, and Communication Team (ERIC) of the Compañía de Jesús, which published that 77% of the population agrees with extradition and only 21.7% shows little to no support for extradition.